All them Witches

Over the past two weeks or so, I’ve watched around 15 movies related to witches, and I’ve enjoyed almost all of them. Now before I share my conclusion of all these witches, here are just a few more films that may have not made it into complete reviews:

The Witches of Eastwick (1987)

This fun and feminist take on witches was probably the best the eighties had to offer on the subject. Based on John Updike’s novel, and directed by George Miller, the film tells the story of three unusual women; Alexandra (Cher), Jane (Susan Sarandon), and Sukie (Michelle Pfeiffer). All three women are outcasts in their society, abandoned by their husbands, and left to rely on each other for emotional support. One night they manage to conjure their ideal male, who also happens to be the devil (Jack Nickolson), and eventually it takes all three of them to try and escape his grip.

The movie is light and fun to watch, the three main ladies are all gorgeous, and it’s heartwarming to see them come together and push each other up. Of course the film still has a whole lot of silly effects and unexplained subplots, but I am sure almost any viewer can overcome that to enjoy the film’s overall cheerful and entertaining atmosphere.

The Love Witch (2016)

I am just gonna start off by saying this movie is weird. Once again this is a feminist take on witches, written, directed, produced, edited, in addition to a bunch of other titles, by Anna Biller, and starring Samantha Robinson as Elaine, a young Wicca witch using love magic to find her perfect match. However, every time Elaine uses her magic to make a man fall in love with her, it seems that they fall so hard it ends killing them. Elaine’s life gets complicated once the police start investigating the death of one of her “lovers”, and the only question that remains is whether her magic can save her this time or simply backfire as usual.

The visuals of this film are just stunning, the colors pop out of the screen, the costumes are meticulously chosen, and overall it’s filled with close ups reminiscent of 1960’s technicolor movies. And yet it is so freaking random, the dialogue is simply a war between the sexes, going back and forth on defining love, and overall it is incredibly campy, from the music to the story to the purposefully cringe worthy performance, everything screams camp. Frankly I didn’t enjoy the movie very much, surely it looked gorgeous, but every single line that was ridiculously over acted made me cringe, but if you have no problems with this kind of art, you should absolutely check it out.

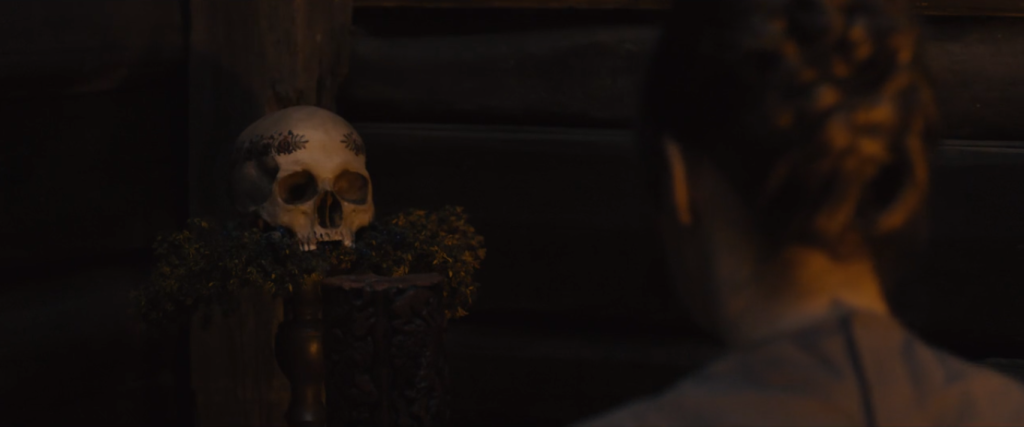

Hereditary (2018)

Ari Aster’s debut feature film received widespread critical acclaim, and with good reason. The film starts after the death of the matriarch of the family, where her daughter Annie (Toni Collette) struggles to overcome both her resentment and curiosity about her late mother. A series of mishaps and tragedies follows, which tears the family apart bit by bit, forcing Annie to dig up her mother’s past, and to try and understand the late woman’s involvement with the occult.

Hereditary carefully examines the theme of mental illness, as Annie’s anxieties stem from her knowledge of her family’s long history of mental problems. The film is a classy piece of horror, keeping the jump scares, and occult elements at a minimum and focusing on its characters’ emotional struggles to deliver a much more effective dose of horror. With Collette’s incredibly powerful performance, and Ari Aster’s sharp directorial style, the film is definitely worth watching.

Midsommar (2019)

The second film from Ari Aster is equally incredible, and I simply couldn’t choose just one. The events of Midsommar take place in Sweden, where a group of American friends are invited to attend a once in a lifetime event; a midsummer festival by a pagan cult called Hårga. Two of the Americans; Dani (Florence Pugh) and Christian (Jack Reynor) are a couple in very strained relationship, and as their relationship deteriorates, the wildness of the festival simply amplifies, culminating in a rather shocking ending for all parties.

Unlike his previous film, Aster placed the cult front and center in Midsommar, and although Dani and Christian’s relationship remains at the heart of the movie, the film extensively explores the psychology of people living in cults, and even the kind of emotional support they might get from it. Filled with psychedelic sequences, as hallucinogenic tea is simply a part of the cult’s everyday life, as well as disturbing pagan rituals, Midsommar manages to lure its viewer into the unsettling and often gruesome community of Hårga.

I guess this is the end of this series, and as much as I wish you’ll check all of the films mentioned, I suppose a roundup of the best films is necessary. I think it’s important to view Rosemary’s Baby (1968), other than the fact that it’s an absolute classic, its exploration of motherhood is exceptional, and is bound to intrigue any viewer. Belladonna of Sadness (1973) is also a must-watch, simply because it is absolutely gorgeous. The Witch (2015) is a slow burn that depends on atmosphere and historical accuracy to tell its sinister folk tale. Finally I think the most realistic representation of witches would have to be Hagazussa (2017); if you’re interested in the history of witchcraft, and a logical explanation for the burning of hundreds of women on the stake, then this is the most honest answer. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ll just go watch cartoons for the rest of the month.